1. What is Formal Theorem Proving ?

Writing rigorous proofs has always been a challenging task that lies at the core of Mathematics. However, with theorems getting more and more complex, it takes months if not years to verify handwritten (informal) proofs. This challenge opens up a new window for automation by writing proofs and verifying proofs in a formal way. Besides mathematics, there are many more applications for writing formal proofs including the writing of certified programs in situations where we want a correctness guarantee for software.

However, writing proofs formally has been a daunting task given the amount of verbosity needed for it to be verifiable by a machine. It takes years’ worth of human work to write formal proofs. For example, it took multiple human years to finish the proofs for CompCert which is a verified compiler for C language. Despite all the difficulties involved, people have started moving towards writing formal proofs using proof assistants or Interactive Theorem Provers (ITPs). These are software tools designed to help humans write verbose proofs in a verifiable language. However, even with these assistants, it is too cumbersome to write complex proofs in formal languages. This makes it absolutely necessary to automate this task or at least provide greater assistance to humans who are writing such formal proofs.

There are multiple languages for theorem proving like Coq, Lean, Isabelle, ACL2, etc.

theorem mod_arith_2

(x : N) : x % 2 = 0 → (x * x) % 2 = 0 :=

begin

intro h,

rw nat.mul_mod,

rw h,

rw nat.zero_mul,

refl,

end

The figure above shows an example of proof written in Lean 3. This is a proof of the fact that for all natural numbers $x$, if $x$ is even then $x^2$ is also even.

(* Natural number definition. As per the definition, 3 = (S (S (S O)) *)

Inductive N : Set := O : N (*Zero is a natural number*)

| S : N -> N. (*S is a function that returns the next natural number *)

(* addition over two natural numbers is defined recursively *)

Fixpoint add (n m : N) : N := match n with

| O => m (* base case *)

| S n_minus_one => S (add n_minus_one m) (* recursive case *)

end.

(* Adding a natural number to zero gives back the same natural number *)

Theorem add_n_O : forall n : N, add n O = n.

Proof.

(*[Goal]<forall n : N, add n O = n>*)

intros n.

(*[NextGoal]<add n O = n>*)

(*[Goal]<add n O = n>*)

induction n.

(*[NextGoal]<add O O = O>*)

(*[Goal]<add O O = O>*)

simpl.

(*[NextGoal]<O = O>*)

(*[Goal]<O = O>*)

reflexivity.

(*[NextGoal]<add (S n) O = S n>*)

(*[Goal]<add (S n) O = S n>*)

simpl.

(*[NextGoal]<S (add n O) = S n>*)

(*[Goal]<S (add n O) = S n>*)

rewrite -> IHn.

(*[NextGoal] <S n = S n> *)

(*[Goal]<S n = S n> *)

reflexivity.

(*[NextGoal]<Proof finished>*)

Qed.

The figure above shows a formal proof written in Coq language, and how the proof goal changes with application of each proof-tactic. This also shows the formalization of natural numbers and a simple proof of the fact that for all natural numbers $n$, $n + 0 = n$.

2. Automatic Theorem Proving History

2.1 Proof Theory: Brief History

The proof theory tries to represent proofs as formal mathematical objects which can then be analyzed using mathematical tools. The formalization of proofs was first attempted by David Hilbert and Paul Bernays in their book called “Grundlagen der Mathematik” in 1934-36. However, the mechanization of proofs was not successfully attempted until the 1970s when Nqthm was created by Boyer and Moore. Nqthm was the precursor to ACL2. ACL2 has been widely used in the industry, for example, by AMD to verify the correctness of floating-point operations. Later in the twenty-first century, more sophisticated proof languages like Coq and Lean were developed.

2.1 Automation and ITPs

Since we can express proofs in a formal language, it seems natural to describe the problem of proving as a search problem. The search space is the set of all possible proofs which can be written in this formal language. However, the search space is too large to be explored by a human. This is where automation comes into the picture. Automation can be used to explore the search space and find proofs. This is the idea behind Automated Theorem Proving (ATP).

2.2 ATP and Machine Learning:

Given the vast space of possible proofs in formal language. It seems reasonable to use ML to narrow down the search space for finding proofs. We can categorize the work done in this field into the following categories:

- Guided Proof Search

- Train for Next Proof-Step Prediction + Search for sequence of proof-steps: These approaches use supervised learning for predicting the next-proof step and then use this trained model to guide a search technique, e.g., best-first or depth-limited search, that synthesizes a proof. These methods were first based off on small slace neural networks (Yang & Deng, 2019; Sanchez-Stern et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2019) as predictors. More recent methods, such as GPT-f (Polu & Sutskever, 2020), PACT (Han et al., 2021), HyperTree Proof Search (Lample et al., 2022), and REPROVER (Yang et al., 2023), have used LLMs.

- Proof prediction using informal proofs: The approach Draft-Sketch-Proof (Jiang et al., 2022) method relies on informal proofs to generate formal proofs.

- Proof prediction using error signals: Methods like Baldur (First et al., 2023) generate the whole proof in one shot using an LLM and then repair it.

- End-to-End Proof Search: These methods use reinforcement learning to directly search for proofs. Kaliszyk et al. (2018) pioneered the use of RL in theorem-proving; subsequently, Wu et al. (2021) gave TacticZero, a deep RL approach to the problem.

2.3. Use of LLMs as Language Agents

Several distinct LLM agent architectures have been proposed over the last year (AutoGPT; ReAct by Yao et al., 2022; Reflection by Shinn et al., 2023; Voyager by Wang et al., 2023). These models combine an LLM’s capability to use tools (Toolformer by Schick et al. (2023)), decompose tasks into subtasks, and self-reflect.

4. CoPrA: in-COntext PRover Agent

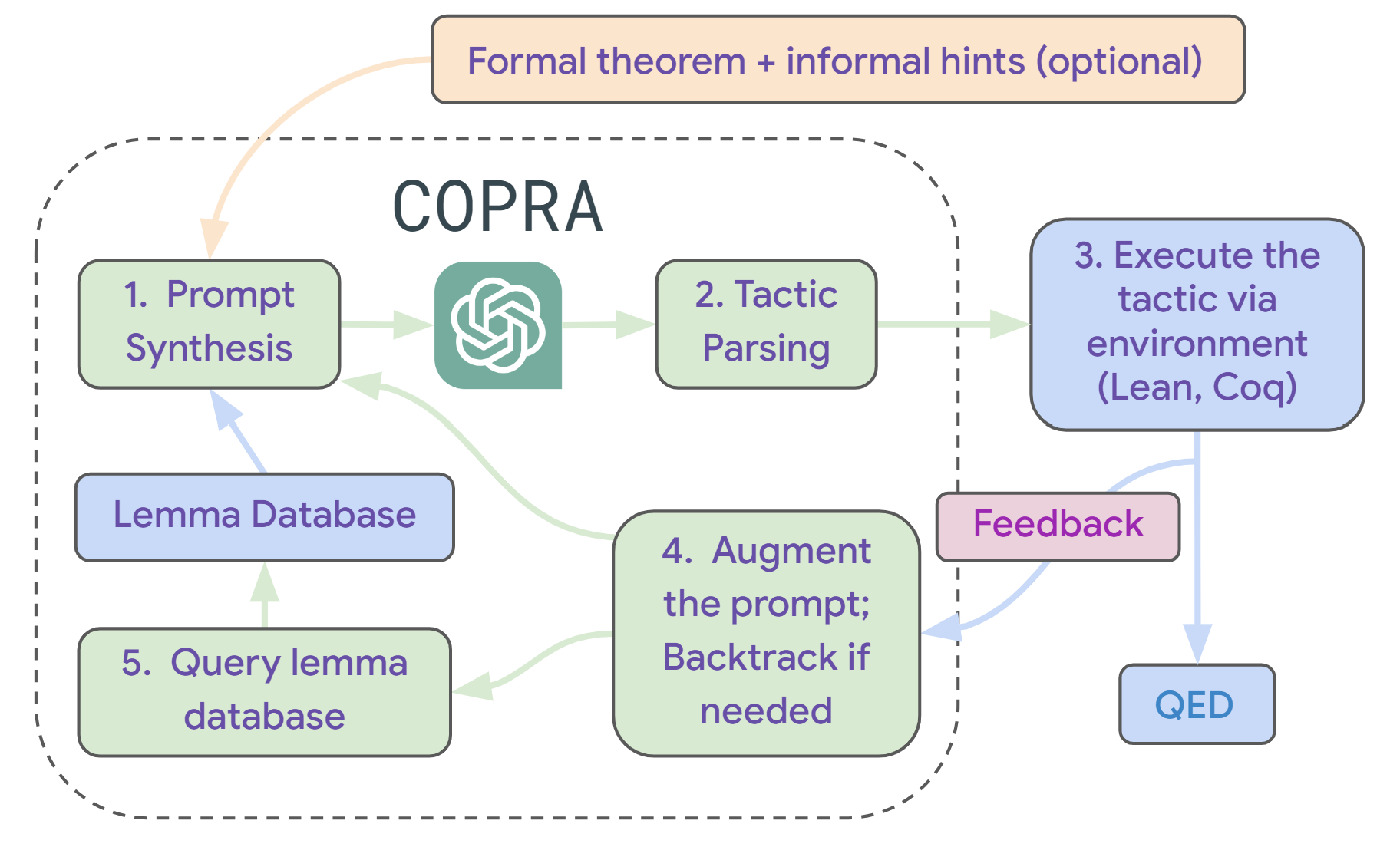

We introduce a new approach in-Context Prover Agent (COPRA) which is a in-Context agent for ATP.

The image above shows how our approach works. The agent takes as input a formal statement of a theorem and optional natural-language hints about how to prove the theorem. At each time step, it prompts the LLM to select the next tactic to apply. LLM-selected tactics are “executed” in the underlying proof assistant. If the tactic fails, \copra records this information and uses it to avoid future failures. Additionally, the agent uses lemmas and definitions retrieved from an external database to simplify proofs. For more details refer to our paper: An In-Context Learning Agent for Formal Theorem-Provin (CoPrA).

(On a side-note: Copra actually means the dried, white flesh of the coconut from which coconut oil is extracted)

4.1 Approach

Abstractly, our proof environment consists of:

- A set of states $\mathcal{O}$. Here,

a state is either a set $O = {o_1,\dots, o_k}$ of

obligations $o_i$, or of the form $(O, w)$, where $O$ is a set of obligations and $w$ is a textual error message. States of the latter form are error states, and the set of such states is denoted by

$\mathit{Err}$. - A set of initial states, each consisting of a single obligation $(g_{in}, h_{in})$ extracted from a user-provided theorem.

- A unique goal state $\mathtt{QED}$ is the empty obligation set.

- A finite set of proof tactics.

-

A transition function $T(O, a)$, which determines the result of applying a tactic $a$ to a state $O$. If $a$ can be successfully applied at state $O$, then $T(O, a)$ is the new set of obligations resulting from the application. If $a$ is a “bad” tactic, then $T(O, a)$ is an error state $(O, w_e)$, where $w_e$ is some feedback that explains the error. Error states $(O, w)$ satisfy the property that $T((O, w), a) = (O, w)$ for all $a$.

- A set of global contexts, each of which is a natural-language string that describes the theorem to be proven and insights (Jiang et al., 2022) about how to prove it. The theorem-proving agent can take a global context as an optional input and may use it to accelerate search.

We define the transition function $T$ to tactic sequences as:

\(T(O, \alpha) =

\left\{\begin{array}{l}

T(O, a_1) \qquad \textrm{if $n = 1$} \\

T(T(O, \langle a_1,\dots, a_{n-1} \rangle), a_n) ~~~ \textrm{otherwise.}

\end{array}

\right.\)

The theorem-proving problem is now defined as follows:

Problem Theorem-proving

Given an initial state $O_{in}$ and an optional global context $\chi$, find a tactic sequence $\alpha$ (a proof) such that $T(O_{in}, \alpha) = \mathit{QED}$.

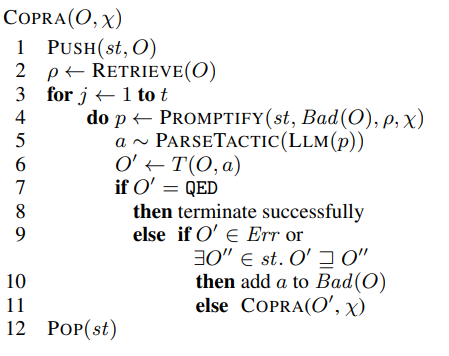

The search procedure in $\texttt{COPRA}$. $T$ is the environment’s transition function; $\mathit{st}$ is a stack, initialized to be empty. $\mathit{Bad}(O)$ is a set of tactics, initialized to $\emptyset$, that are known to be bad at $O$. $\texttt{Llm}$ is an LLM, $Prompt$ generates a prompt, $Action$ parses the output of the LLM into a tactic (repeatedly querying the LLM in case there are formatting errors in its output), and $Retrieve$ gathers relevant lemmas and definitions from an external source. The overall procedure is called with a state $O_{in}$ and an optional global context $\chi$.

A “conversation” between the LLM and the search algorithm in $\texttt{COPRA}$. Query $#1$, Query $#2$, $\dots$ represent queries made as the proof search progresses. The column labeled Query $#i$ depicts the prompt at time step $i$ and the corresponding LLM response. The LLM response is parsed into a tactic and executed, with the error feedback incorporated into the next prompt.

4.2 Evaluation

We evaluated our approach on two datasets: miniF2F and CompCert which belong to different domains mathematics and software verification respectively.

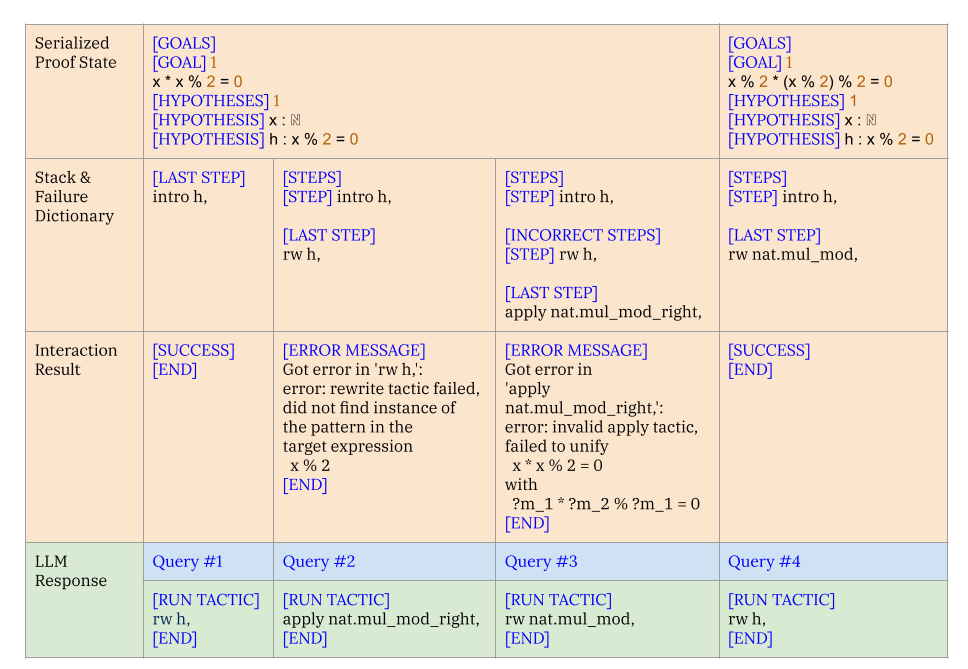

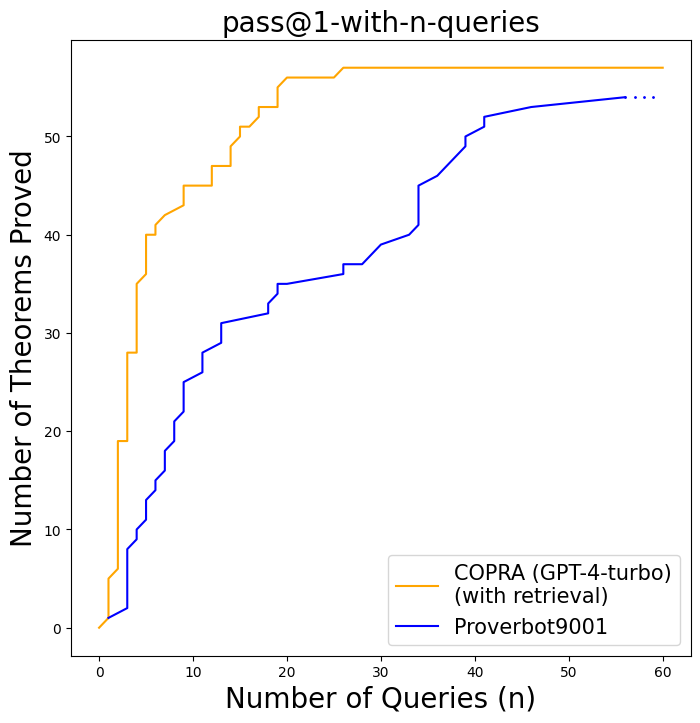

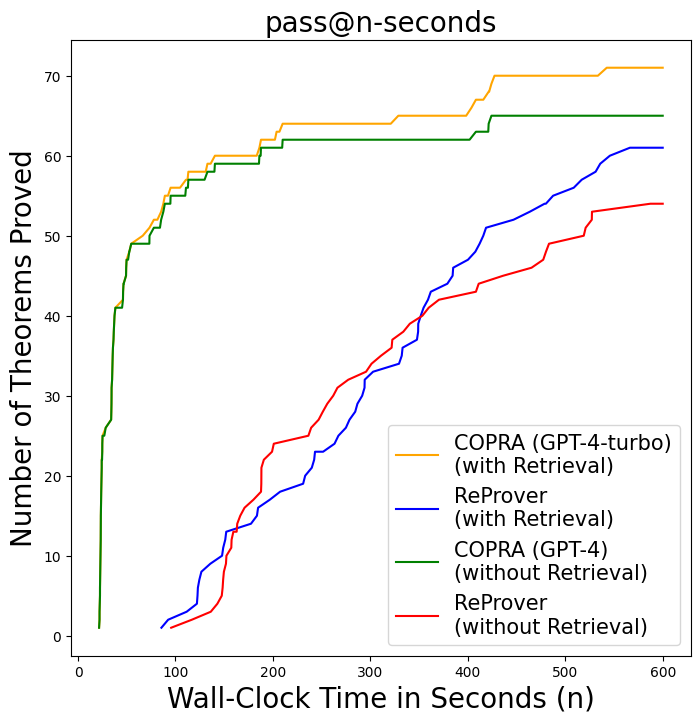

We use a metric called “Pass@k-with-n-queries” while comparing our approach with ReProver and Proverbot9001. The standard metric for evaluating theorem-provers is pass@k (Lample et al., 2022). In this metric, a prover is given a budget of $k$ proof attempts; the method is considered successful if one of these attempts leads to success. We consider a refinement of this metric called pass@k-with-n-queries. Here, we measure the number of correct proofs that a prover can generate given k attempts, each with a budget of $\texttt{n}$ queries from the LLM or neural model. We enforce that a single query includes exactly one action (a sequence of tactics) to be used in the search. We want this metric to be correlated with the number of correct proofs that the prover produces within a specified wall-clock time budget; however, the cost of an inference query on an LLM is proportional to the number of responses generated per query. To maintain the correlation between the number of inference queries and wall-clock time, we restrict each inference on the LLM to a single response.

The figure shows, comparison between ReProver and our approach on miniF2F dataset. It shows that not only $\texttt{COPRA}$ solves more problems than ReProver, but it also does that in lesser number of queries. $\texttt{COPRA}$ solves almost all problems solved by ReProver in less than 60 queries.

The figure shows, comparison between Proverbot9001 and our approach on CompCert dataset. We show that $\texttt{COPRA}$ works well across domains (theorem proving in software verification as well as formal mathematics).

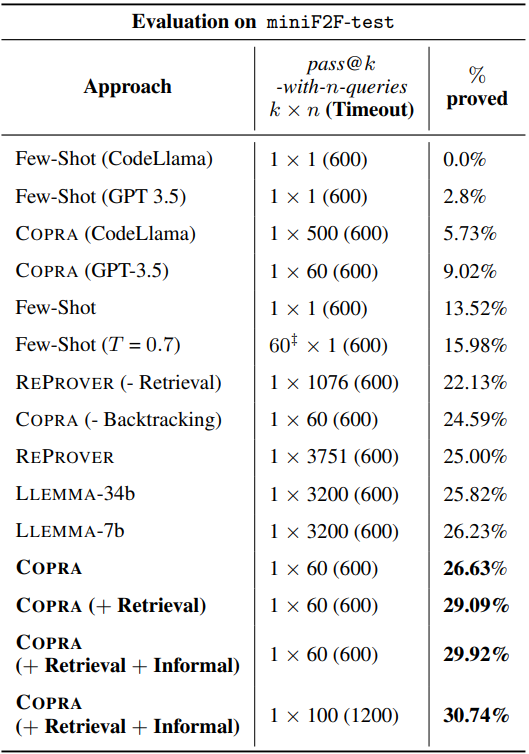

The tables below shows a detailed comparison of our approach with other approaches.

Aggregate statistics for $\texttt{COPRA}$ and the baselines on $\texttt{miniF2F}$ dataset. Note the various ablations of $\texttt{COPRA}$ with and without retrieval or informal proofs. The timeout is a wall-clock time budget in seconds allocated across all attempts. Unless otherwise specified, (i) $\texttt{COPRA}$ uses GPT-4 as the LLM (ii) the temperature ($T$) is set to 0.

We show that pass@k-with-n-queries, correlates very well with wall-clock time for finding proofs by using the metric pass@k-seconds. pass@k-seconds measures the number of proofs that an approach can find in less than $k$ seconds. The plot shows that pass@k-seconds follows the same trend as pass@k-with-n-queries.

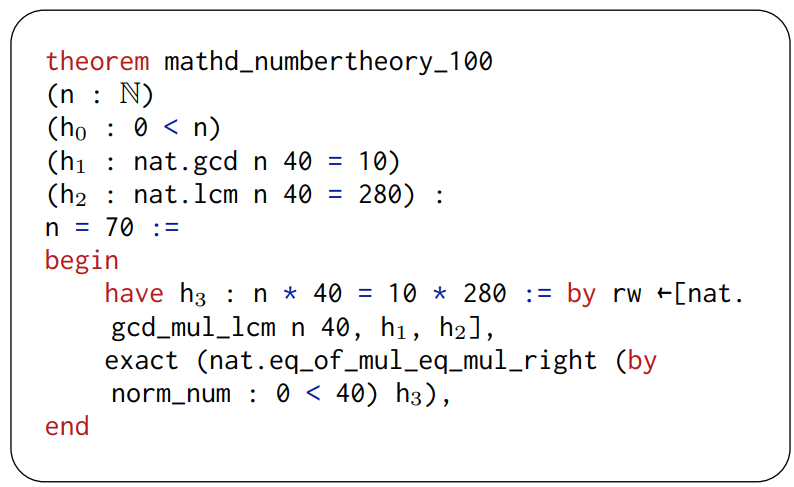

4.3 Some interesting proofs found by CoPrA

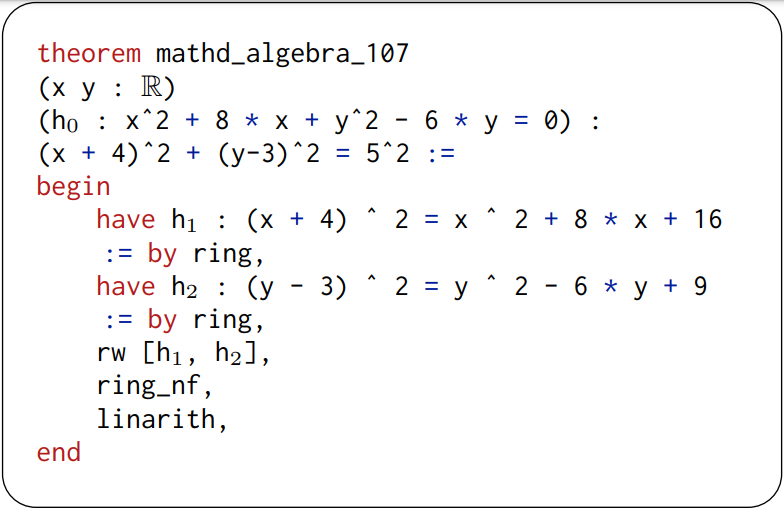

A theorem in the “numbertheory” category that $\texttt{COPRA}$ could prove but $\texttt{ReProver}$ could not. $\texttt{COPRA}$ could prove this result because of retrieval. BM25 retrieval found the lemma $\texttt{pnat.gcd_mul_lcm} : (\texttt{n}\; \texttt{m} : \mathbb{N}+) : (\texttt{gcd}\;\texttt{n}\;\texttt{m}) * (\texttt{lcm}\;\texttt{n}\;\texttt{m}) = \texttt{n} * \texttt{m}$ which helped $\texttt{COPRA}$ to prove the theorem above.

An interesting proof generated by $\texttt{COPRA}$ while using informal proofs hints generated via GPT-4.

Some other interesting proofs generated for $\texttt{miniF2F}$ by $\texttt{COPRA}$. The length of the proofs generated shows that interaction with the environment helps in fixing the errors encountered while writing long proofs. These long sequences of rewrites are not easy to synthesize without knowing the exact execution feedback from the environment which often contains the hint to fix the rewrites.

![]()

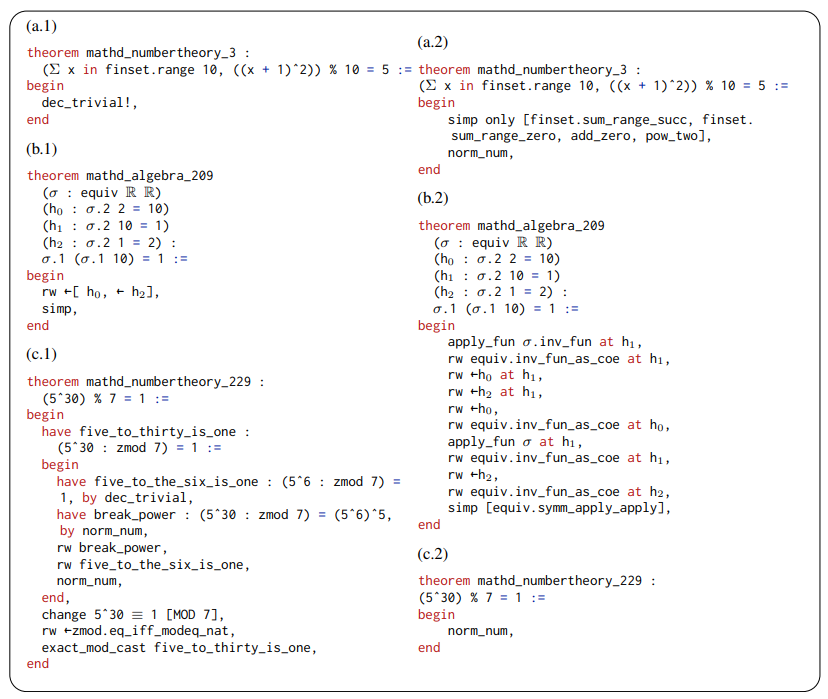

Some interesting proofs generated for $\texttt{miniF2F}$ dataset which were generated because of $\texttt{COPRA}$’s backtracking capabilities.

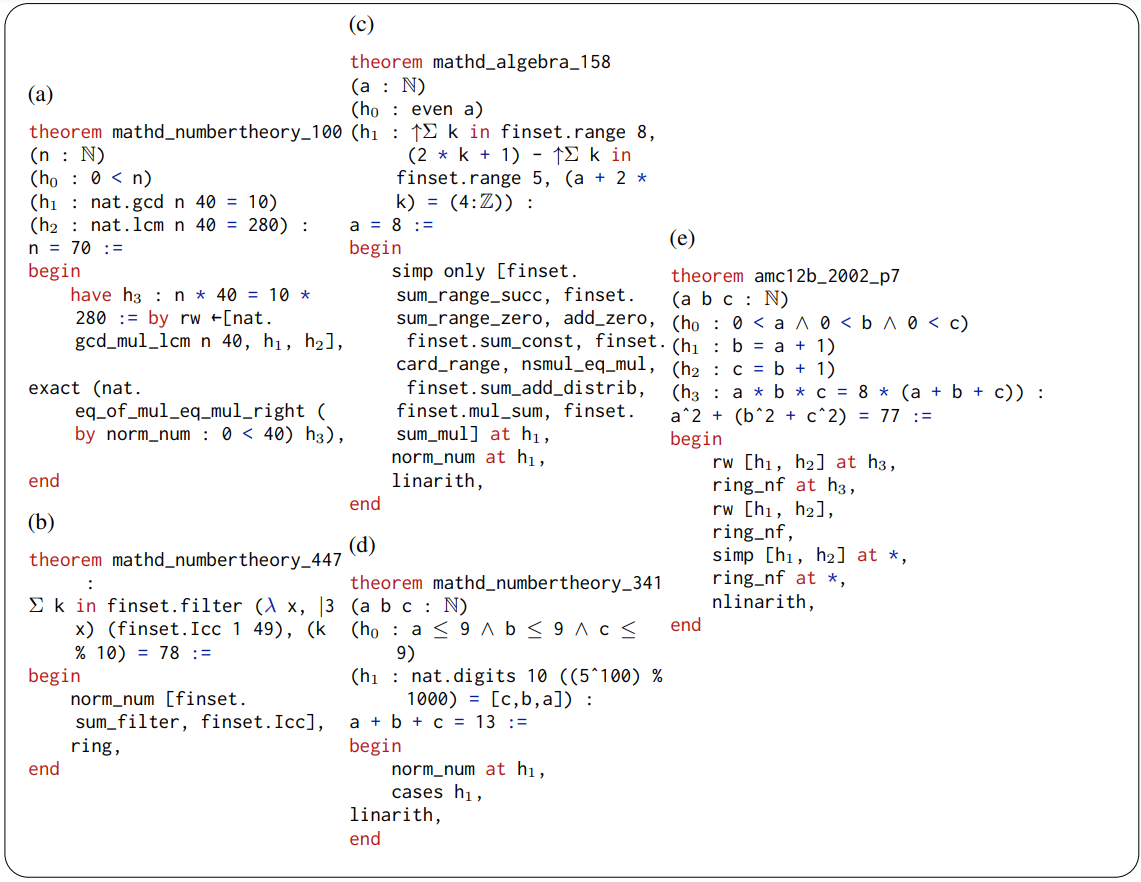

Some proofs found by $\texttt{COPRA}$ as compared to the proofs mentioned in the $\texttt{miniF2F}$ test dataset. It is interesting to see that the proofs generated by $\texttt{COPRA}$ are different from the proofs mentioned in the repository. This is especially true when the proofs are longer. It is also worth noting that occasionally $\texttt{COPRA}$ can find very simple proofs for longer proofs mentioned in $\texttt{miniF2F}$ test dataset. (a.1), (b.1), and (c.1) show the proofs as mentioned in the $\texttt{miniF2F}$ dataset, while (a.2), (b.2), and (c.2) show the corresponding proofs generated by $\texttt{COPRA}$.

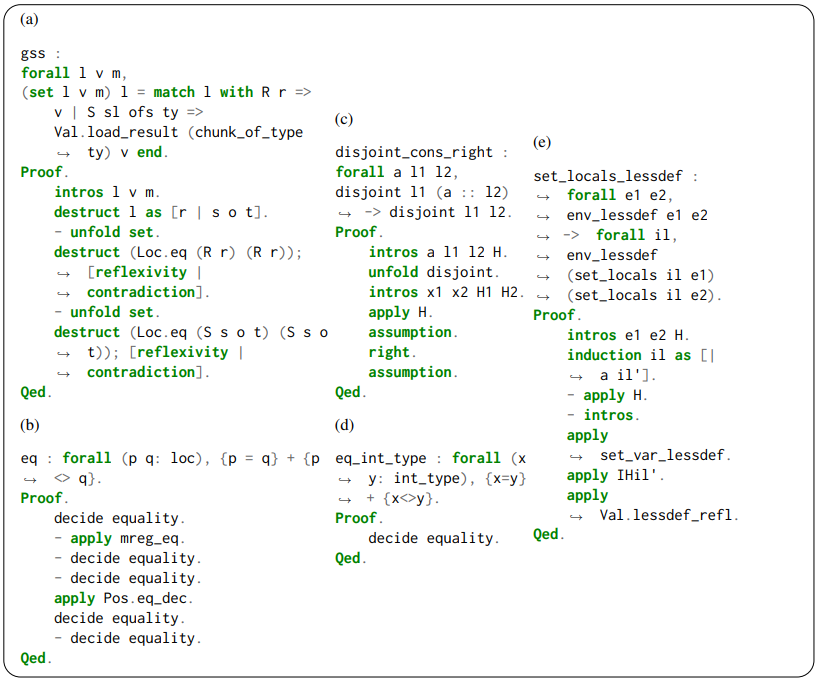

Some other interesting proofs generated for CompCert by $\texttt{COPRA}$. We can see that these proofs are long, and often use “apply” tactic which shows that $\texttt{COPRA}$ can effectively use the retrieved information to discharge given proof states.